From time to time I publish metrics on vulnerabilities that affect Red Hat Enterprise Linux. One of the more interesting metrics looks at how far in advance we know about the vulnerabilities we fix, and from where we get that information. This post is abstracted from the upcoming "4 years of Enterprise Linux 4" risk report

For every fixed vulnerability across every package and every severity in Enterprise Linux 4 AS in the first 4 years of its life, we determined if the flaw was something we knew about a day or more in advance of it being publicly disclosed, and how we found out about the flaw.

For vulnerabilities which are already public when we first hear about them we still track the source as it's a useful internal indicator on where the security response team should focus their efforts.

So from this data, Red Hat knew about 51% of the security vulnerabilities that we fixed at least a day in advance of them being publicly disclosed. For those issues, the average notice was 21 calendar days, although the median was much lower, with half the private issues having advance notice of 9 days or less.

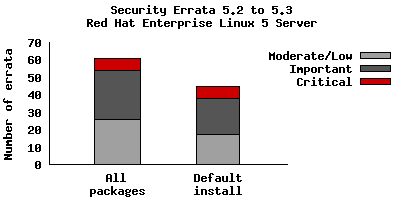

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5.3 was released today, around 8 months since the release of 5.2 in May 2008. So let's use this opportunity to take a quick look back over the vulnerabilities and security updates we've made in that time, specifically for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 Server.

The chart below shows the total number of security updates issued for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 Server as if you installed 5.2, up to and including the 5.3 release, broken down by severity. I've split it into two columns, one for the packages you'd get if you did a default install, and the other if you installed every single package (which is unlikely as it would involve a bit of manual effort to select every one). So, for a given installation, the number of packages and vulnerabilities will probably be somewhere between the two.

So for a default install, from release of 5.2 up to and including 5.3, we shipped 45 advisories to address 127 vulnerabilities. 7 advisories were rated critical, 21 were important, and the remaining 17 were moderate and low.

For all packages, from release of 5.2 to and including 5.3, we shipped 61 advisories

to address 181 vulnerabilities. 7 advisories were rated critical, 28 were

important, and the remaining 26 were moderate and low.

The 7 critical advisories were for just 3 different packages:

- Five updates to Firefox (July, July, September, November, December) where a malicious web site could potentially run arbitrary code as the user running Firefox. Given the nature of the flaws, ExecShield protections in RHEL5 should make exploiting these memory flaws harder.

- An update to Samba (May), where a remote attacker who can connect and send a print request to a Samba server could cause a heap overflow. The Red Hat Security Response Team believes it would be hard to remotely exploit this issue to execute arbitrary code due to the default enabled SELinux targeted policy and the default enabled SELinux memory protection tests. We are not aware of any public exploit for this issue.

- An update to OpenSSH (August), provided to mitigate an intrusion into certain Red Hat computer systems. The attacker was able to sign a small number of tampered packages but they were not distributed on the Red Hat Network. We classified this update as critical to ensure any tampered packages would be replaced with official packages.

Although not of critical severity, also of interest during this period were the spoofing attacks on DNS servers. We provided an update to BIND (July) adding source port randomization to help mitigate these attacks.

Updates to correct all of these critical vulnerabilities (as well as migitate the BIND issue) were available via Red Hat Network either the same day, or one calendar day after the issues were public.

In fact for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 since release and to date, every critical vulnerability has had an update available to address it available from the Red Hat Network either the same day or the next calendar day after the issue was public.

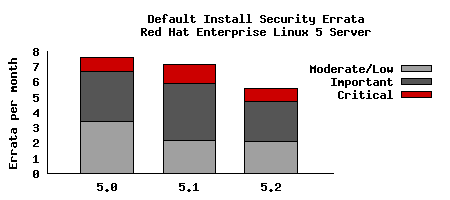

To compare this with the last updates we need to take into account that the time between each update is different. So looking at a default installation and calculating the number of advisories per month gives the following chart:

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 shipped with a number of security technologies designed to make it harder to exploit vulnerabilities and in some cases block exploits for certain flaw types completely. For 5.2 to 5.3 there were two flaws blocked that would otherwise have required updates:

- A double-free flaw in unzip. The glibc pointer checking limited the exploitability of this issue to just a crash of unzip, a client application, which does not have security implications. No security update was needed.

- Two format string flaws in c++filt. The format string protection caused these issues to have no security implications. No security update was needed.

This data is interesting to get a feel for the risk of running Enterprise Linux 5 Server, but isn't really useful for comparisons with other versions, distributions, or operating systems -- for example, a default install of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 4AS did not include Firefox, but 5 Server does. You can use our public security measurement data and tools, and run your own custom metrics for any given Red Hat product, package set, timescales, and severity range of interest.

See also:5.1 to 5.2 risk report

Secunia collect some very interesting information about the patch state of Windows systems. Their results from 20,000 machines published yesterday were that over 98% of PCs were insecure, having at least one out-of-date application installed.

Actually this isn't surprising and is exactly what I'd expect; it's all down to third party applications.

Let's say you're browsing the web. It's more than likely that at some point you'll want to view some PDF files, watch some Flash content, or play a Java game. Those tasks are all dealt with by third party applications, although to the end user it's all part of the browser experience. Since your system is only as secure as its weakest link, you need to manage security updates for those third party applications just as carefully as you manage security updates for the rest of your system. That's why Adobe Reader, Java, Flash, and all the myriad of other applications you've installed in order to make your system useful have their own update mechanisms. Some applications on Windows will 'phone home' when they are run and check to see if they need to be updated, others deploy services that sit in the background looking for updates from time to time, others even check every time your system starts. Many don't get automated updates at all.

How do you deal with all that risk? I believe it's possible by providing an OS distribution which includes all the bits you'll likely need to make a useful computing environment, thereby taking away that update uncertainty. Red Hat ship several PDF viewers in our distributions for example, but we also ship (in an Extras channel) Adobe Reader. Our Security Response Team are monitoring for security issues in everything we ship, all the third party applications, and providing a single point of contact, a single notification system, and a single way to get the updates.

If Microsoft knew that say 25% of all their users installed Firefox, wouldn't they be better bundling it and providing their centralised automated updates for it, to reduce their customers overall risk? They do already bundle some third party applications, although it's been with mixed success as we found 3 years ago when they didn't provide security fixes for bundled Flash (ZDNet coverage).

This is, in part, why you've not seen me respond recently to the Vista security reports which compare vulnerability counts. In these reports they use a cut-down minimal Red Hat Enterprise Linux installation in order to make it look more like Windows for the comparisons. But this is completely backwards -- the fact that we're including and fixing the flaws using a common process in so much third party software is actually helping reduce the risk and protect real customers. For example we could easily cut our vulnerability count by shipping only one PDF viewer instead of four. But if we know that these other viewers are going to get installed by the customer anyway all we've done is to hide the vulnerability count elsewhere, and you've made the customers overall risk increase.

So it may seem counter-intuitive but we should ship as much third party applications (that we know people use) as we can, because a single managed security update and notification process will decrease a users overall risk. The fewer third party applications that users have to get from elsewhere and install and manage for themselves the better in my opinion.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5.2 was released last week, around 6 months since the release of 5.1 in November 2007. So let's use this opportunity to take a quick look back over the vulnerabilities and security updates we've made in that time, specifically for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 Server.

The graph below shows the total number of security updates issued for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 Server starting at 5.1 up to and including the 5.2 release, broken down by severity. I've split it into two columns, one for the packages you'd get if you did a default install, and the other if you installed every single package (which is unlikely as it would involve a bit of manual effort to select every one). So, for a given installation, the number of packages and vulnerabilities will probably be somewhere between the two.

So for a default install, from release of 5.1 up to and including 5.2, we shipped 46 updates to address 119 vulnerabilities. 8 advisories were rated critical, 24 were important, and the remaining 14 were moderate and low.

For all packages, from release of 5.1 to and including 5.2, we shipped 62 updates to address 179 vulnerabilities. 9 advisories were rated critical, 29 were important, and the remaining 24 were moderate and low.

The nine critical updates were in five different packages:

- Four updates to Firefox (November, February, March, April) where a malicious web site could potentially run arbitrary code as the user running Firefox. Given the nature of the flaws, ExecShield protections in RHEL5 should make exploiting these memory flaws harder.

- An update to the GnuTLS library (May), where

a remote attacker who can connect to a server making use of GnuTLS could

cause a buffer overflow. In Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5, the CUPS print

server uses GnuTLS.

- An update to MIT Kerberos (March),

where a remote attacker who can conect to the krb5kdc or kadmind

services could cause a buffer overflow.

- An update to OpenPegasus

(January), where

a remote attacker who can connect to OpenPegasus could cause a buffer overflow.

The Red Hat Security Response Team believes that it would be hard to remotely

exploit this issue to execute arbitrary code, due to the default SELinux

targeted policy, and the default SELinux memory protection tests.

- Two updates to Samba (November, December) where a remote attacker who can connect to the Samba port could cause buffer overflows. In addition to ExecShield making this harder to exploit, the impact of any sucessful exploit would be reduced as Samba is constrained by an SELinux targeted policy (enabled by default).

Updates to correct all of these critical issues were available via Red Hat Network either the same day, or one calendar day after the issues were public.

To get a better idea of risk we need to look not only at the vulnerabilities but also the exploits written for those vulnerabilities. A proof of concept exploit exists publicly for one of the Samba flaws, CVE-2007-6015, but we are not aware of public exploits for any other of those critical vulnerabilities. Also of high risk was an important "zero-day" exploit affecting the Linux kernel where a local unprivileged user could gain root privileges. Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5.1 was affected and a fix was available two calendar days after public disclosure.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 shipped with a number of security technologies designed to make it harder to exploit vulnerabilities and in some cases block exploits for certain flaw types completely. For the period of this study there were two flaws blocked that would otherwise have required updates:

- A double-free flaw in CUPS. The glibc pointer checking limited the exploitability of this issue to just a crash of CUPS and not the ability to execute arbitrary code. code execution. We still issued an update, as a remote attacker could trigger this flaw and cause CUPS to crash.

- An uninitialized pointer free flaw in unzip, caught by the glibc pointer checking. As exploitation of this flaw results in just a crash of a user application, no updates were needed.

This data is interesting to get a feel for the risk of running Enterprise Linux 5 Server, but isn't really useful for comparisons with other versions or distributions -- for example, a default install of Red Hat Enterprise 4AS did not include Firefox. You can get the results I presented above for yourself by using our public security measurement data and tools, and run your own custom metrics for any given Red Hat product, package set, timescales, and severities.

See also 5.0 to 5.1 risk report

It sometimes seems like the Security Response Team at Red Hat are pushing security updates every day, but actually a default installation of Enterprise Linux 4 AS was vulnerable to only 7 critical security issues in the first three years since release. But to get a picture of the risk you need to do more than count vulnerabilities.

My full risk report was published yesterday in Red Hat Magazine and reveals the state of security since the release of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 4 including metrics, key vulnerabilities, and the most common ways users were affected by security issues.

"Red Hat knew about 49% of the security vulnerabilities that we fixed in advance of them being publicly disclosed. For those issues, the average notice was 21 calendar days, although the median was much lower, with half the private issues having advance notice of 8 days or less."

Secunia released a security summary report for 2007 and surprisingly gave a count for Red Hat for the year at over 600 vulnerabilities. I had no idea how they got to this number, it certainly doesn't match our own publicly available metrics at https://www.redhat.com/security/data/metrics

Using our public tool, for every Red Hat product and service, for 2007 we issued 306 advisories to fix 404 vulnerabilities. Of those 404 vulnerabilities 41 were critical (on the scale used by Microsoft and Red Hat).

Most people are not going to be using every Red Hat product, so taking just Enterprise Linux product you find 348 vulnerabilities, of which 27 were critical. A given user is going to only be vulnerable to the issues that affect the products and packages they have installed. Using the scripts on our pages you can figure it out for your own circumstances. But as an example, the default installation of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 4 AS had 172 vulnerabilities of which 4 were critical.

The Secunia report does actually make it clear you can't use their vulnerability count as a method of comparing platforms, in part due to the differences in methodology of the vendors, but I'm sure this won't stop some press from jumping to conclusions if they don't read the actual report.

I've asked Secunia how they got to their number of vulnerabilities, but in the meantime, a raw count of vulnerabilities is only a small part of the overall risk exposure in using a product. I've got some more reports that go into this in more detail for two years of Enterprise Linux 4 and Enterprise Linux 5.0 to 5.1.

Update: Coverage of this: ZDNet

Update: Secunia told me that they treat each advisory separately; so for example yesterday we issued updates for some moderate severity issues in the Apache Web server, but we did separate advisories for each affected product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 2.1, 3, 4, 5, Red Hat Application Stack v1, v2. So in this case the same Apache vulnerability would be counted 6 times.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5.1 was released today, around 8 months since the release of 5.0 in March 2007. So let's use this opportunity to take a quick look back over the vulnerabilities and security updates we've made in that time, specifically for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 Server.

The graph below shows the total number of security updates issued for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 Server up to and including the 5.1 release, broken down by severity. I've split it into two columns, one for the packages you'd get if you did a default install, and the other if you installed every single package (which is unlikely as it would involve a bit of manual effort to select every one). So, for a given installation, the number of packages and vulnerabilities will be somewhere between the two extremes.

So for all packages, from release up to and including 5.1, we shipped 94 updates to address 218 vulnerabilities. 7 advisories were rated critical, 36 were important, and the remaining 51 were moderate and low.

For a default install, from release up to and including 5.1, we shipped 60 updates to address 135 vulnerabilities. 7 advisories were rated critical, 26 were important, and the remaining 27 were moderate and low.

- These figures include ten updates we released on the day we shipped 5.0. This was because we froze package updates some months before releasing the product. Only one of those updates was rated critical, an update to Firefox.

- The six other critical updates were:

- Three more updates to Firefox (May, July, October) where a malicious web site could potentially run arbitrary code as the user running Firefox. Given the nature of the flaws, ExecShield protections in RHEL5 should make exploiting these memory flaws harder.

- An update to the Kerberos telnet deamon (April) A remote attacker who can access the telnet port of a target machine could log in as root without requiring a password. None of the standard protection mechanisms help prevent exploitation of this issue, however the krb5 telnet daemon is not enabled by default in Enterprise Linux 5 and the default firewall rules block remote access to the telnet port. This flaw did not affect the more common telnet daemon distributed in the telnet-server package.

- An update to Samba (May) where a remote attacker could cause a heap overflow. In addition to ExecShield making this harder to exploit, the impact of any sucessful exploit would be reduced as Samba is constrained by an SELinux targeted policy (enabled by default).

- An update to the PCRE library (November). This was labelled critical because the Konqueror web browser uses PCRE to handle regular expressions in JavaScript, and therefore a user browsing a malicious site in Konqueror could trigger this issue. (Konqueror is not part of a default install, but I've left this issue as critical in the results).

- Updates to correct all of these critical issues were available via Red Hat Network within a day of the issues being public.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 shipped with a number of security technologies designed to make it harder to exploit vulnerabilities and in some cases block exploits for certain flaw types completely. For the period of this study there were two flaws blocked that would otherwise have required critical updates:

- A stack buffer overflow flaw in the RPC library in Kerberos. This flaw was blocked by FORTIFY_SOURCE which removed the possibility of remote code execution. We still issued an update, as a remote attacker could trigger this flaw and cause Kerberos to crash.

- Another flaw in Kerberos, this time due to the free of an invalid pointer. This flaw was blocked by glibc, although a remote attacker could still cause a crash, so we issued an update.

This data is interesting to get a feel for the risk of running Enterprise Linux 5 Server, but isn't really useful for comparisons with other versions or distributions -- for example, a default install of Red Hat Enterprise 4AS did not include Firefox. You can get the results I presented above for yourself by using our public security measurement data and tools, and run your own metrics for any given Red Hat product, package set, timescales, and severities.

Back in August I found that many of the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) scores that the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) assigned to vulnerabilities affecting open source software were incorrect.

Since then I've been sending in corrections on a monthly basis, taking into account the worst possible score across all affected platforms (and not how Red Hat products were affected specifically).

For the five months May to September 2007 I looked at 178 vulnerabilities (across all Red Hat products and services). Only 80 were accurate. Corrections were submitted to NVD and they fixed the incorrect CVSS scores on the remaining 98 vulnerabilities.

So, before the corrections, there were 65 issues rated "High" out of 178. After the corrections there are actually only 17 rated "High".

Fortunately the number of corrections needed each month seems to be decreasing, but we'll continue to send in corrections every month. Even with the corrections, the severity rating for a given vulnerability may well vary for the version each vendor ships; so you need to be careful if you are basing your risk assesments soley on the accuracy of third-party severity ratings.

The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) assign a severity rating to every vulnerability; "High", "Medium", or "Low". The rating is determined by ranges of CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System) v2 scores. I've not been a big fan of CVSS: I don't think it works particularly well when applied to software that is shipped by multiple vendors, or for open source software and libraries that don't know all the possible use-cases of their software.

Even though I'm not a fan, NVD publish a CVSS score for every issue, security companies are using those scores in their vulnerability feeds to customers, and people are using them for metrics. So it's important that these scores are accurate.

I decided to take a look at how accurate the CVSS scores were, so for every vulnerability we fixed in any Red Hat product for June 2007 examined the CVSS score given by NVD. For each one figuring out if the CVSS base metrics were correct, and where they were not submitting the correction back to NVD. This analysis of the vulnerabilities was based on their possible worst-case threat to all platforms (I didn't adjust the CVSS scores for how the issues affected Red Hat products specifically).

There were 39 total vulnerabilities for which unfortunately only 8 scores were accurate. I submitted corrections to NVD and they fixed the CVSS scores on the remaining 31 vulnerabilities.

20 vulnerabilities ended up moving down in ranking, 6 vulnerabilities moved up, and 5 stayed the same (although the CVSS score changed).

Before the corrections there were 14 issues rated "High" out of 39, after the corrections there are just 3 rated "High".

Those corrections are now live in the NVD, and I really appreciate how quick the folks behind NVD were at checking and making the changes. I've submitted to them corrections for a couple more months too, and I'll write about those when there complete. Unfortunately it does take a lot of time to investigate each issue and do the corrections, so it will limit how far back into 2007 we can correct.

Although Red Hat is well known for Red Hat Enterprise Linux we actually have a large number of other supported products, both layered on top of Enterprise Linux (like Red Hat Application Stack) and stand-alone (like Red Hat Directory Server). The majority of these products are serviced through the Red Hat Network and get our security advisories in a standard way and are included in the Security Response Team metrics. But our analysis scripts were not particularly consistent in dealing with product names.

Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) is a naming scheme designed to combat these inconsistencies, and is part of the 'making security measurable' initiative from Mitre. From today we're supporting CPE in our Security Response Team metrics: we publish a mapping of Red Hat advisories to both CVE and CPE platforms (updated daily) and you can use CPE to filter the metrics. Some examples of CPE names:

cpe://redhat:enterprise_linux:5:server/firefox -- the Firefox browser package on Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 server.

cpe://redhat:enterprise_linux:3 -- Red Hat Enterprise Linux 3

cpe://redhat/xpdf -- the xpdf package in any Red Hat product.

cpe://redhat:rhel_application_stack:1 -- Red Hat Application Stack version 1