Moving my email archives to Ponymail went well

One feature I forgot that zoe had was how it indexed some attachments. If you have an email with a PDF attachment and that PDF attachment had plain text in it (it wasn't just a scan) then you could search on words in the PDF. That's super handy. Ponymail doesn't do that, in fact you don't get to search on any text in attachments, even if they are plain text (or things like patches). Let's fix that!

Remember how I said whenever I need some code I first look if there is an Apache community that has a project that does something similar? Well Apache Tika is an awesome project that will return the plain text of pretty much whatever you throw at it. PDF? sure. Patches? definitely. Word docs? yup. Images? yes. Wait, images? so Tika will go and use Tesseract and do an OCR of an image.

Okay, so let's add a field to the mbox index, attachmenttext, populate it with Tika, and search on it. For now if some text in an attachment matches your search query you'll see the result, but you won't know exactly where the text appears (perhaps later it could highlight which attachment it appears in).

I wrote a quick Python script that runs through all emails in Ponymail (or some search query subset), and if they have attachments runs all the attachments through Apache Tika, storing the plain texts in the attachmenttext field. We ignore anything that's already got something in that field, so we can just run this periodically rather than on import. Then a one-line patch to Ponymail also searches the attachmenttext field. 40,000 attachments and two hours later, it was all done and working.

It's not ready for a PR yet; probably for Ponymail upstream we'd want the option of doing this at import, although I chose not too so we can be deliberately careful as parsing untrusted attachments is risky

So there we have it; a way to search your emails including inside most attachments, outside the cloud, using Open Source projects and a few little patches.

I have a lot of historical personal email, back as far as 1991, and from time to time there's a need to find some old message. Although services like GMail would like to you keep all your mail in their cloud and pride themselves on searching, I'd rather keep my email archive offline and encrypted at rest unless there's some need to do a search. Indeed I always use Google takeout every month to remove all historic GMail messages. Until this year I used a tool called Zoe for allowing searchable email archives. You can import your emails, it uses Apache Lucene as a back end, and gives you a nice web based interface to find your mails. But Zoe has been unmaintained for over a decade and has mostly vanished from the net. It was time to replace it.

Whenever I need some open source project my first place to look is if there is an Apache Software Foundation community with a project along the same lines. And the ASF is all about communities communicating over Email, so not only is there an ASF project with a solution, but that project is used to provide the web interface for all the archived ASF mailing lists too. "Ponymail Foal" is the project and lists.apache.org is where you can see it running. (Note that the Ponymail website refers to the old version of Pony Mail before "Foal")

Internally the project is mostly Python, HTML and Javascript, using Python scripts to import emails into elasticsearch, so it's really straightforward to get up and running following the project instructions.

So I can just import my several hundred thousand email messages I have in random text mbox format files and be done? Well, nearly. It almost worked but it needed a few tweaks:

- Bad "Content-Type" headers. Even my bank gets this wrong with the header Content-Type: text/html; charset="utf-8 charset=\"iso-8859-1\"". I just made the code ignore similar bad headers and try the fallbacks. Patch here

- Messages with no text or HTML body and no attachments. These are fairly common for example a calendar entry might be sent as "Content-Type: text/calendar". I just made it so that if there is no recognised body it just uses whatever the last section it found was, regardless of content type. Patch here

- Google Chat messages from many years ago. These have no useful anything, no body, no to: no message id, no return address. Rather than note them as failures I use made the code ignore them completely. Since this is just a warning, no upstream patch prepared.

Managing a personal email archive can be a daunting task especially with the volume of email correspondence. However, with Ponymail, it's possible to take control of your email archive, keep it local and secure, and search through it quickly and efficiently using the power of ElasticSearch.

My GPG key has lasted me well, over 18 years, but it's a v2 key and therefore no longer supported by newer versions of GnuPG. So it's time to move to a new one. I've made a transition statement available. If you signed my old key please consider signing the new one.

I've written about why OpenSSL chose the disclosure method we did for the CCS Injection issues and how it went here

Here is the timeline from my (OpenSSL) perspective for the recent CCS Injection (MITM) vulnerability as well as the other flaws being fixed today.

SSL/TLS MITM vulnerability (CVE-2014-0224)

- 2014-04-22 (Date we were told the reporters shared the issue with JPCERT/CC)

- 2014-05-01 JPCERT/CC make first contact with OpenSSL security

- 2014-05-02 JPCERT/CC send detailed report and reproducer to OpenSSL security (issue details are not complete and doesn't look possible for a general purpose MITM at this point)

- 2014-05-09 CERT/CC make first contact with OpenSSL security and send an updated report and reproducer which shows full MITM is possible

- 2014-05-09 OpenSSL verify the issue and assign CVE-2014-0224

- 2014-05-12 JPCERT/CC contact OpenSSL with updated reproducer

- 2014-05-13 OpenSSL start communication directly to reporters to share updated patch and other technical details

- 2014-05-21 JPCERT/CC notify OpenSSL they have notified "vendors who have implemented OpenSSL in their products" under their framework agreement

- 2014-05-21 CERT/CC request permission to prenotify vendors of the issue

- 2014-05-21 OpenSSL work with two major infrastructure providers to test the fix and ensure the fix is sufficient

- 2014-06-02 CERT/CC notify their distribution list about the security update but with no details

- 2014-06-02 "OS distros" private vendor list is given headsup and ability to request the patches and draft advisory (0710). Told Red Hat (0710) Debian (0750) FreeBSD (0850), AltLinux (1050), Gentoo (1150), Canonical (1150), IBM (1700), Oracle (1700), SUSE (2014-06-03:0820), Amazon AMI (2014-06-03:1330), NetBSD/pkgsrc (2014-06-04:0710), Openwall (2014-06-04:0710)

- 2014-06-02 Red Hat find issue with patch (1400), updated patch sent to vendors

- 2014-06-02 Canonical find regression with patch (1700), Stephen produces updated patch, sent to vendors (1820)

- 2014-06-03 "ops-trust" (1015) and selected OpenSSL Foundation contracts (0820) are told a security update will be released on 2014-06-05 but with no details

- 2014-06-05 Security updates and advisory is released (1130)

DTLS recursion flaw (CVE-2014-0221)

- 2014-05-09 Reporter contacts OpenSSL security

- 2014-05-09 OpenSSL contacts reporter with possible patch for verification

- 2014-05-16 Reporter confirmes patch

- 2014-05-18 OpenSSL tells reporter CVE name

- 2014-06-02 "OS distros" notification as above

- 2014-06-03 OpenSSL lets reporter know the release date

- 2014-06-05 Security updates and advisory is released

DTLS invalid fragment vulnerability (CVE-2014-0195)

- 2014-04-23 HP ZDI contact OpenSSL security and pass on security report

- 2014-05-29 OpenSSL let ZDI know the release date

- 2014-06-02 "OS distros" notification as above

- 2014-06-05 Security updates and advisory is released

Anonymous ECDH denial of service (CVE-2014-3470)

- 2014-05-28 Felix Gröbert and Iva Frantić at Google report to OpenSSL

- 2014-05-29 OpenSSL tell reporters CVE name and release date

- 2014-06-02 "OS distros" notification as above

- 2014-06-05 Security updates and advisory is released

Post copied from my original source on Google+ https://plus.google.com/u/0/113970656101565234043/posts/L8i6PSsKJKs

We've had more than a few press enquiries at OpenSSL about the timeline of the CVE-2014-0160 (heartbleed) issue. Here's the OpenSSL view of the timeline:

-

April 01 - Google contact the Google OpenSSL team members with details of the

issue and a patch. This was forwarded to the OpenSSL core team members (1109

UTC). Original plan was to push that week, but it was postponed until April 09

to give time for proper processes. Google tell us they've notified some

infrastructure providers under embargo, we don't have the names or dates for

these.

(Due to my unfortunate-timed holiday this week I used my Security Response Team members at Red Hat to help co-ordinate this issue on behalf of OpenSSL, but see below for when Red Hat Engineering were formally notified and started working on the issue for Red Hat)

- April 07 (0556 UTC) OpenSSL (via me) notify Red Hat. Red Hat internal bug created. This is the time Red Hat was officially notified under embargo, engineers and the Red Hat Security Response Team started working on the issue.

- April 07 (0610 UTC) Red Hat contact the private distros list (https://oss-security.openwall.org/wiki/mailing-lists/distros ) and let them know an OpenSSL issue is due on Wednesday (no details of the issue are given: just affected versions. Vendors are told to contact Red Hat for the full advisory under embargo.

- April 07 - OpenSSL (via Red Hat) give details of the issue, advisory, and patch to the OS vendors that replied -- under embargo, telling them the issue will be public on April 09. This was SuSE (0815 UTC), Debian (0816 UTC), FreeBSD (0849 UTC), AltLinux (1000 UTC). Some other OS vendors replied but we did not give details in time before the issue was public, these included Ubuntu (asked at 1130 UTC), Gentoo (1414 UTC), Chromium (1615 UTC).

- April 07 (1519 UTC) - CERT-FI contact me and Ben Laurie by encrypted email with details of the same issue found by Codenomicon. This was forwarded to the OpenSSL core team members (1611 UTC)

- April 07 - The coincidence of the two finds of the same issue at the same time increases the risk while this issue remained unpatched. OpenSSL therefore released updated packages that day.

- April 07 (1725 UTC) OpenSSL updates, web pages including vulndb, and security advisory (1839 UTC) gets made public.

(Originally posted in Google+ at https://plus.google.com/u/0/113970656101565234043/posts/TmCbp3BhJma )

Note: Akamai note on their blog that they were given advance notice of this issue by the OpenSSL team. This is incorrect. They were probably notified directly by one of the vulnerability finders.

Note: To see how this fits into the overall timeline of this issue see this article

Here is a quick writeup of the protocol for the iKettle taken from my Google+ post earlier this month. This protocol allows you to write your own software to control your iKettle or get notifications from it, so you can integrate it into your desktop or existing home automation system.

The iKettle is advertised as the first wifi kettle, available in UK since February 2014. I bought mine on pre-order back in October 2013. When you first turn on the kettle it acts as a wifi hotspot and they supply an app for Android and iPhone that reconfigures the kettle to then connect to your local wifi hotspot instead. The app then communicates with the kettle on your local network enabling you to turn it on, set some temperature options, and get notification when it has boiled.

Once connected to your local network the device responds to ping requests and listens on two tcp ports, 23 and 2000. The wifi connectivity is enabled by a third party serial to wifi interface board and it responds similar to a HLK-WIFI-M03. Port 23 is used to configure the wifi board itself (to tell it what network to connect to and so on). Port 2000 is passed through to the processor in the iKettle to handle the main interface to the kettle.

Port 2000, main kettle interface

The iKettle wifi interface listens on tcp port 2000; all devices that connect to port 2000 share the same interface and therefore receive the same messages. The specification for the wifi serial board state that the device can only handle a few connections to this port at a time. The iKettle app also uses this port to do the initial discovery of the kettle on your network.Discovery

Sending the string "HELLOKETTLE\n" to port 2000 will return with "HELLOAPP\n". You can use this to check you are talking to a kettle (and if the kettle has moved addresses due to dhcp you could scan the entire local network looking for devices that respond in this way. You might receive other HELLOAPP commands at later points as other apps on the network connect to the kettle.Initial Status

Once connected you need to figure out if the kettle is currently doing anything as you will have missed any previous status messages. To do this you send the string "get sys status\n". The kettle will respond with the string "sys status key=\n" or "sys status key=X\n" where X is a single character. bitfields in character X tell you what buttons are currently active:| Bit 6 | Bit 5 | Bit 4 | Bit 3 | Bit 2 | Bit 1 |

| 100C | 95C | 80C | 65C | Warm | On |

So, for example if you receive "sys status key=!" then buttons "100C" and "On" are currently active (and the kettle is therefore turned on and heating up to 100C).

Status messages

As the state of the kettle changes, either by someone pushing the physical button on the unit, using an app, or sending the command directly you will get async status messages. Note that although the status messages start with "0x" they are not really hex. Here are all the messages you could see:

| sys status 0x100 | 100C selected |

| sys status 0x95 | 95C selected |

| sys status 0x80 | 80C selected |

| sys status 0x100 | 65C selected |

| sys status 0x11 | Warm selected |

| sys status 0x10 | Warm has ended |

| sys status 0x5 | Turned on |

| sys status 0x0 | Turned off |

| sys status 0x8005 | Warm length is 5 minutes |

| sys status 0x8010 | Warm length is 10 minutes |

| sys status 0x8020 | Warm length is 20 minutes |

| sys status 0x3 | Reached temperature |

| sys status 0x2 | Problem (boiled dry?) |

| sys status 0x1 | Kettle was removed (whilst on) |

You can receive multiple status messages given one action, for example if you turn the kettle on you should get a "sys status 0x5" and a "sys status 0x100" showing the "on" and "100C" buttons are selected. When the kettle boils and turns off you'd get a "sys status 0x3" to notify you it boiled, followed by a "sys status 0x0" to indicate all the buttons are now off.

Sending an action

To send an action to the kettle you send one or more action messages corresponding to the physical keys on the unit. After sending an action you'll get status messages to confirm them.

| set sys output 0x80 | Select 100C button |

| set sys output 0x2 | Select 95C button |

| set sys output 0x4000 | Select 80C button |

| set sys output 0x200 | Select 65C button |

| set sys output 0x8 | Select Warm button |

| set sys output 0x8005 | Warm option is 5 mins |

| set sys output 0x8010 | Warm option is 10 mins |

| set sys output 0x8020 | Warm option is 20 mins |

| set sys output 0x4 | Select On button |

| set sys output 0x0 | Turn off |

Port 23, wifi interface

The user manual for this document is available online, so no need to repeat the document here. The iKettle uses the device with the default password of "000000" and disables the web interface.If you're interested in looking at the web interface you can enable it by connecting to port 23 using telnet or nc, entering the password, then issuing the commands "AT+WEBS=1\n" then "AT+PMTF\n" then "AT+Z\n" and then you can open up a webserver on port 80 of the kettle and change or review the settings. I would not recommend you mess around with this interface, you could easily break the iKettle in a way that you can't easily fix. The interface gives you the option of uploading new firmware, but if you do this you could get into a state where the kettle processor can't correctly configure the interface and you're left with a broken kettle. Also the firmware is just for the wifi serial interface, not for the kettle control (the port 2000 stuff above), so there probably isn't much point.

Missing functions

The kettle processor knows the temperature but it doesn't expose that in any status message. I did try brute forcing the port 2000 interface using combinations of words in the dictionary, but I found no hidden features (and the folks behind the kettle confirmed there is no temperature read out). This is a shame since you could combine the temperature reading with time and figure out how full the kettle is whilst it is heating up. Hopefully they'll address this in a future revision.Security Implications

The iKettle is designed to be contacted only through the local network - you don't want to be port forwarding to it through your firewall for example because the wifi serial interface is easily crashed by too many connections or bad packets. If you have access to a local network on which there is an iKettle you can certainly cause mischief by boiling the kettle, resetting it to factory settings, and probably even bricking it forever. However the cleverly designed segmentation between the kettle control and wifi interface means it's pretty unlikely you can do something more serious like overiding safety (i.e. keeping the kettle element on until something physically breaks).

"Before" and "After" video:

We were looking for a cheap laser lighting effect for our weekend parties and saw one that looked impressive, the Lanta Quasar Buster 2, and for only £30 new. The unit has both a red and green laser and and a nice moving effect that looks like the beams splits up and recombine again. It promised "sound activation" and we thought that meant it would do some clever sound to light effect, but it really does mean sound activation and just turns itself on when it hears a sound, then off again when it's silent. So out of the box the laser has three modes; the first lets you just set the speed of the effect with the lasers constantly on, the second strobes the lasers on and off to a speed you can set, and the third is the usless sound activation mode.

Warrany void if removed. I didn't technically "remove" the sticker though.

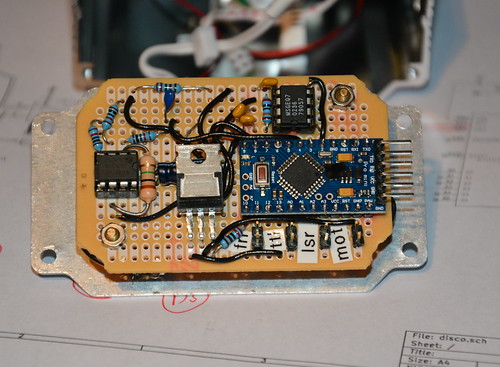

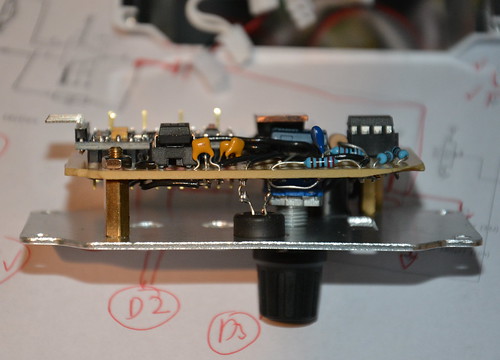

Opening the unit showed that it was easily hackable; all the connections to the control panel were via connectors. One connector provides +5v to the cooling fan, another +5v to a separate board that handles powering the two lasers, another connects to the motor the turns the optics to produce the burst effect, and the final one has a logic level signal to tell the laser power board if the lasers should be on or off.

Since the laser power board is completely separate we can just replace this control panel with one of our own and then we can control the laser on/off and the speed of the motor (actually we could control the direction too but it doesn't really make the effect look any better so I leave it as one direction). And we can always swap the original board back in the future.

My new control board comprises of an Arduino pro mini compatible board, a rotary encoder for setting the mode and levels, a mic with simple opamp preamp, and a MSGEQ7 chip to do all the hard work of analysing the levels of various frequencies. The optics motor is now simply driven using a PWM output via a MOSFET I had spare.

Rough source and circuit diagram are available from github; some components don't have values if it doesn't really matter and others (like the MOSFET) can be changed as I just used things I happened to have in my component boxes. I'm still playing with different effects in software to see what works best.

You can read my Enterprise Linux 6.3 to 6.4 risk report on the Red Hat Security Blog.

"for all packages, from release of 6.3 up to and including 6.4, we shipped 108 advisories to address 311 vulnerabilities. 18 advisories were rated critical, 28 were important, and the remaining 62 were moderate and low."

"Updates to correct 77 of the 78 critical vulnerabilities were available via Red Hat Network either the same day or the next calendar day after the issues were public. The other one was in OpenJDK 1.60 where the update took 4 calendar days (over a weekend)."

And if you are interested in how the figures were calculated, here is the working out:

Note that we can't just use a date range because we've pushed some RHSA the weeks before 6.4 that were not included in the 6.4 spin. These issues will get included when we do the 6.4 to 6.5 report (as anyone installing 6.4 will have got them when they first updated).

So just after 6.4 before anything else was pushed that day:

** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 server (all packages) ** Dates: 20101110 - 20130221 (835 days) ** 397 advisories (C=55 I=109 L=47 M=186 ) ** 1151 vulnerabilities (C=198 I=185 L=279 M=489 ) ** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Server (default installation packages) ** Dates: 20101110 - 20130221 (835 days) ** 177 advisories (C=11 I=71 L=19 M=76 ) ** 579 vulnerabilities (C=35 I=133 L=159 M=252 )And we need to exclude errata released before 2013-02-21 but not in 6.4:

RHSA-2013:0273 [critical, default] RHSA-2013:0275 [important, not default] RHSA-2013:0272 [critical, not default] RHSA-2013:0271 [critical, not default] RHSA-2013:0270 [moderate, not default] RHSA-2013:0269 [moderate, not default] RHSA-2013:0250 [moderate, default] RHSA-2013:0247 [important, not default] RHSA-2013:0245 [critical, default] RHSA-2013:0219 [moderate, default] RHSA-2013:0216 [important, default] Default vulns from above: critical:12 important:2 moderate:16 low:3 Non-Default vulns from above: critical:4 important:2 moderate:5 low:0This gives us "Fixed between GA and 6.4 iso":

** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 server (all packages) ** Dates: 20101110 - 20130221 (835 days) ** 386 advisories (C=51 I=106 L=47 M=182 ) ** 1107 vulnerabilities (C=182 I=181 L=276 M=468 ) ** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Server (default installation packages) ** Dates: 20101110 - 20130221 (835 days) ** 172 advisories (C=9 I=70 L=19 M=74 ) ** 546 vulnerabilities (C=23 I=131 L=156 M=236 )And taken from the last report "Fixed between GA and 6.3 iso":

** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 server (all packages) ** Dates: 20101110 - 20120620 (589 days) ** 278 advisories (C=33 I=78 L=31 M=136 ) ** 796 vulnerabilities (C=104 I=140 L=196 M=356 ) ** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Server (default installation packages) ** Dates: 20101110 - 20120620 (589 days) ** 134 advisories (C=6 I=56 L=15 M=57 ) ** 438 vulnerabilities (C=16 I=110 L=126 M=186 )Therefore between 6.3 iso and 6.4 iso:

** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 server (all packages) ** Dates: 20120621 - 20130221 (246 days) ** 108 advisories (C=18 I=28 L=16 M=46 ) ** 311 vulnerabilities (C=78 I=41 L=80 M=112 ) ** Product: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Server (default installation packages) ** Dates: 20120621 - 20130221 (246 days) ** 38 advisories (C=3 I=14 L=4 M=17 ) ** 108 vulnerabilities (C=7 I=21 L=30 M=50 )Note: although we have 3 default criticals, they are in openjdk-1.6.0, but we only call Java issues critical if they can be exploited via a browser, and in RHEL6 the Java browser plugin is in the icedtea-web package, which isn't a default package. So that means on a default install you don't get Java plugins running in your browser, so really these are not default criticals in RHEL6 default at all.

You can read my Enterprise Linux 6.2 to 6.3 risk report on the Red Hat Security Blog.

"for all packages, from release of 6.2 up to and including 6.3, we shipped 88 advisories to address 233 vulnerabilities. 15 advisories were rated critical, 23 were important, and the remaining 50 were moderate and low."And if you are interested in how the figures were calculated, as always view the source of this blog entry."Updates to correct 34 of the 36 critical vulnerabilities were available via Red Hat Network either the same day or the next calendar day after the issues were public. The Kerberos telnet flaw was fixed in 2 calendar days as the issue was published on Christmas day. The second PHP flaw took 4 calendar days (over a weekend) as the initial fix released upstream was incomplete."